If you’re anything like me, thinking about how to structure your reading block is exciting. It’s my favorite time of day. Every summer I find myself daydreaming about the next year… how do I want to structure the reading block? What will I focus on in my small groups? What routines do I want to implement during the whole group? Thinking about how to structure your reading block with the science of reading in mind, however, can be daunting if new to the task.

Reflecting back on how I once answered the above questions, back before my world was flipped upside down with the science of reading, it looked so different from the answers I find myself saying now. I was trained in a balanced literacy approach. I taught a workshop model. The majority of my time was spent in leveled texts and focused on reading “strategies.” Yet as my science of reading research continued, the more I began to question these practices. The science I was reading about didn’t match my practice. This is a hard pill for a teacher to swallow. After all, what teacher wants to be doing wrong by their students. I had to confront the practices I had been relying on. It was time to analyze if what I was doing was really helping my students make the gains they needed to.

If you’re new on your science of reading journey, or just trying to learn more, today I want to talk about some simple things you can rethink when thinking about that big question of “What do I want my reading block to look like?” If you’re new to my blog and haven’t yet downloaded my FREE 7 Ways to Revamp your Reading Instruction Starting Tomorrow, be sure to grab your copy to see 7 simple ways to get started with the science of reading.

In this blog post however, I want to walk you through a series of questions in which you can use to rethink your reading block.

Where should I start when thinking about my reading block?

In recent educational times, there have been two schools of thought in the discussion around how people believe reading should be taught. Those two approaches are code-emphasis and meaning-emphasis. These two approaches can be compared across the multiple facets of how students are learning to read in a typical classroom. Neither approach tends to exclude components of reading instruction; rather they tend to spend their time and focus differently.

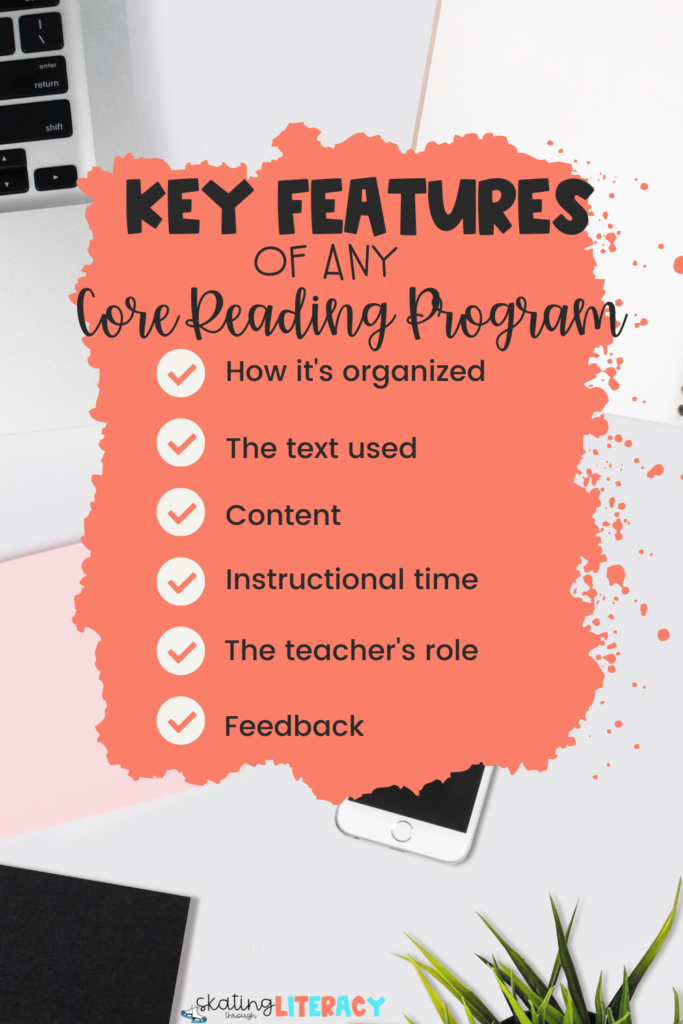

Throughout most core reading programs, there are a few key features to pay attention to: how is the program organized, what texts are used, what type of content is covered, how is instructional time spent, what is the teacher’s role, and how feedback is provided?

How curriculums address each of these key features varies depending on which program you are looking at. As a teacher, the curriculum you have is dependent on the district and state in which you live. You often have very little control over which core reading program you have to teach in your classroom. However, if you understand the key features of each program, you can quickly evaluate it’s effectiveness.

With so much to do, how to I know which parts are critical to my reading block?

Once you understand the features of your core reading program, you can begin to piece together how you want that to unfold in your reading block. According to the National Reading Panel, an effective reading block should include the following:

- An emphasis on oral language, to include vocabulary development

- Phonemic awareness and the teaching of phonics, decoding and word studies

- Learning of a sight vocabulary

- The explicit teaching of comprehension strategies

- Meaningful writing experiences

- The development of fluent reading with opportunities for both guided and independent reading, including informal reading activities

- Reading at the ‘Just-Right’ level

- Access to a wide-range of reading materials

Making sure each of these principles is a part of your reading block is a great start to ensuring your providing high quality instruction to your students.

What is currently a priority during my reading block?

Before you can do any rethinking of your reading block with the science of reading, first you must spend time thinking about how your approach currently looks.

- Is there a mandated curriculum you must follow?

- How does that curriculum address each of these?

- Are you creating the scope and sequence in which you provide instruction for your students?

- How do you personally approach these features of reading instruction?

As busy classroom teachers, it can be almost impossible to find the time to sit down for this reflection. However, evaluating your current classroom practices is critical to making meaningful change moving forward. Sometimes the critical lens that comes from deep reflection can reveal things you were unaware of. What you believe about reading instruction may not be how it actually plays out in your classroom. Or vice versa. So be sure you find some time to answer these questions, before implementing anything dramatically new.

How are my students currently performing?

After considering the key features of your reading block, you need to consider how your students are currently performing. What has led you to rethink or revamp your reading block in the first place? This very data point of how your students are currently performing may reflect the answer to the previous question. We know that, “even when regular classroom instruction (tier 1) is effective, at least 20 percent of the students are still likely to need either small-group (tier 2) or intensive (tier 3) instruction,” (LETRS, Unit 3). However, if more than 20% of your student population is not responding to the tier 1 instruction, then it is in fact time to take a good hard look at your core instruction. This data point is the one that led me to ultimately seeking out the science of reading. The meaning-emphasis approach, or whole language principles, I had been trained on was failing my students.

Once you have identified if your current instruction is effective, then you can make thoughtful decisions about how to structure your reading block. If 20% or less of your students aren’t meeting benchmark, then your tier 1 is performing well. As a result, you may want to focus your efforts on small group instruction. If the number of students not meeting benchmark is much higher than 20%, than your efforts should be focused on tier 1 instruction. You should be focusing on what is happening during whole group instruction and how you can best target the areas of need.

What grade level are you currently teaching?

While this seems like an obvious question to consider when planning your reading block, the importance of the answer is quite possibly deeper than you may have originally imagined. Before my learnings around the science of reading principles, I would have told you “of course I understand that a first grade reading block and a fifth grade reading block would look different.” However, if I was being honest with myself, I did not exactly know how. Obviously a first grader needs different instruction than a fifth grader. But the details of the how had been lost on me. Read longer books, read harder books, write more about their reading, have better discussions? These were all the guesses I would have envisioned.

However, as I dove into research around instructional minutes throughout different grade levels, the data was astonishing. A study done by Foorman & Schastschenider looked at how teachers across the same grade levels spent instructional minutes and compared that to the reading results of the students in their classrooms. The first finding that really amazed me was the drastically different time that individual teachers spent on word work and phonics instruction vs comprehension from classroom to classroom. Here’s what they found across first grade classrooms:

“Observers found that some first grade teachers spent about 40% of their time on word work which included phonological awareness, phonics and decoding, and sight word learning. In those classrooms, students who originally scored ‘at risk’ on the screening tests scored above average in word recognition, phonic decoding, and spelling at the end of first grade. Classroom teachers who spent less than 20% of their time on word work and who heavily emphasized reading comprehension in first grade, had students who were less proficient in basic reading and spelling skills at the end of first grade and second grades who did not show any advantage in reading comprehension at that point.” Findings from Foorman & Schattschneider 2003 Early Interventions Project Data.

The answer to what grade level do you teach is a dramatically important one. The age of your students and current level of development dictates how many minutes you should be allocating to each part of your reading block. These minutes will change throughout different grade levels.

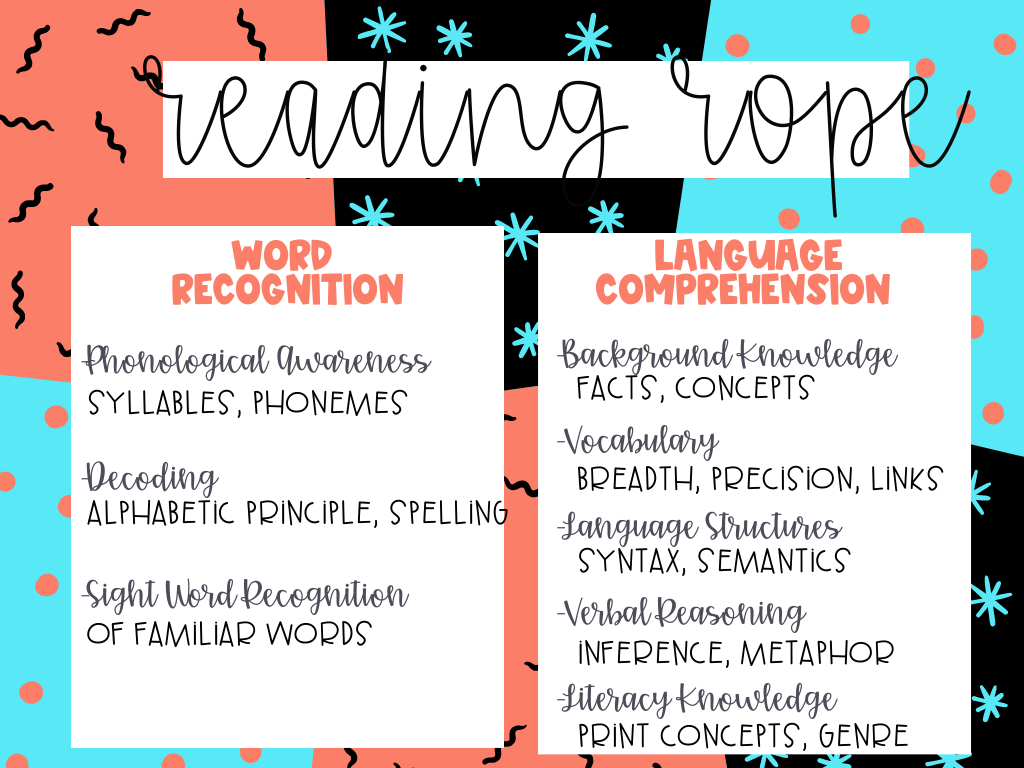

Am I covering all aspects of the reading rope?

Another concept to consider as you examine your reading block is: are you addressing all aspects of Scarborough’s reading rope? Many teachers are beginning to understand that reading is the product of word recognition x language comprehension. However, Scarborough’s rope goes much more in-depth to identify individual aspects of each component. Each of these are worthy of their own moment of reflection.

- How does the curriculum you use cover each of these?

- How can you supplement what you are currently doing to enhance your practice?

What are my science of reading non-negotiables?

Since I’ve now given you a lot of think about and answer when it comes to your reading block and the since of reading, let me give you a peak at how I began this progress. Within my reading block, I’ve developed non-negotiables from my science of reading studies. Everyday I attempt to think of more ways I can incorporate brain research into my reading block. Here are some non-negotiables I’ve begun weaving into our everyday routines.

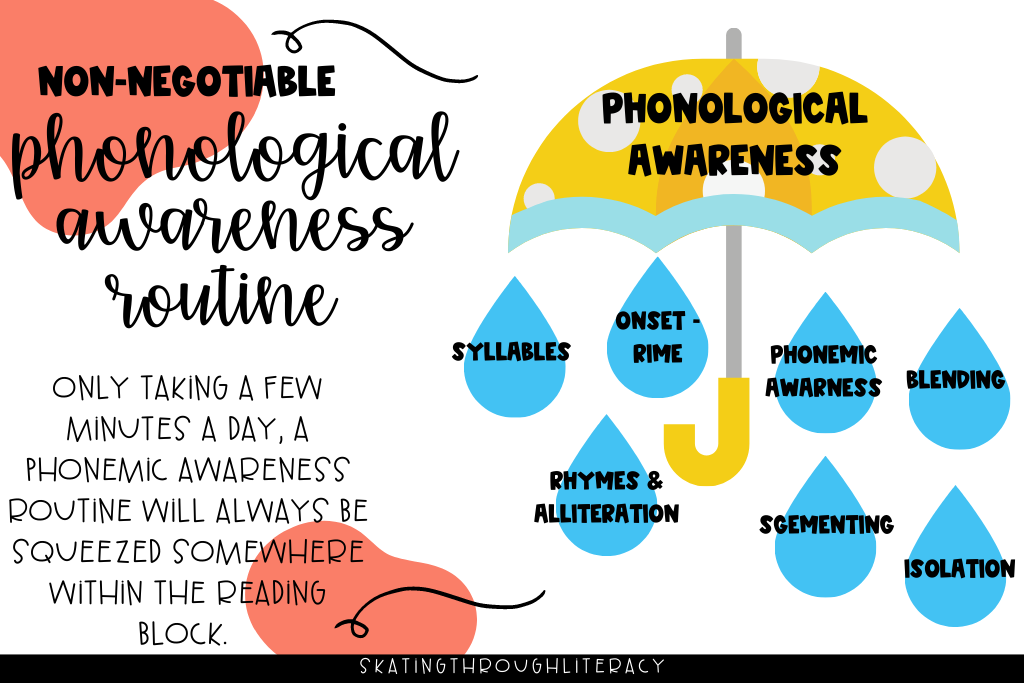

Non-negotiable #1: Phonological Awareness

This is something I knew next to nothing about before the science of reading entered my life. As a third grade teacher, I didn’t see any great value. I often looked at skills like rhyming as a “baby skill” or “kindergarten” skill. But that’s because I simply did not know any better. Now I understand that phonological awareness is how students first develop the skills that will carry them into being successful fluent readers. It’s not important to work in rhyming words simply because it sounds fun. But rather it is building this knowledge of words and sounds that is the very backbone of learning to read. In third grade, phonological awareness looks more like phonemic awareness. This means students are starting to attaching letters to the sounds by using skills like segmenting, blending, isolating, and manipulating.

My favorite part of phonological or phonemic routines in my classroom is that they feel like brain breaks. They are quick, fast, fun and can go anywhere in your block. To add an extra layer of fun, sometimes I will incorporate a song to signal to the students its time for phonemic awareness. This music signal tells them to sit on their desks, close their eyes, and get ready to make some words with our ears and our mouths. Students think they’re playing a fun silly game where they can sit on their desks. And I can squeeze in some valuable practice without them even knowing.

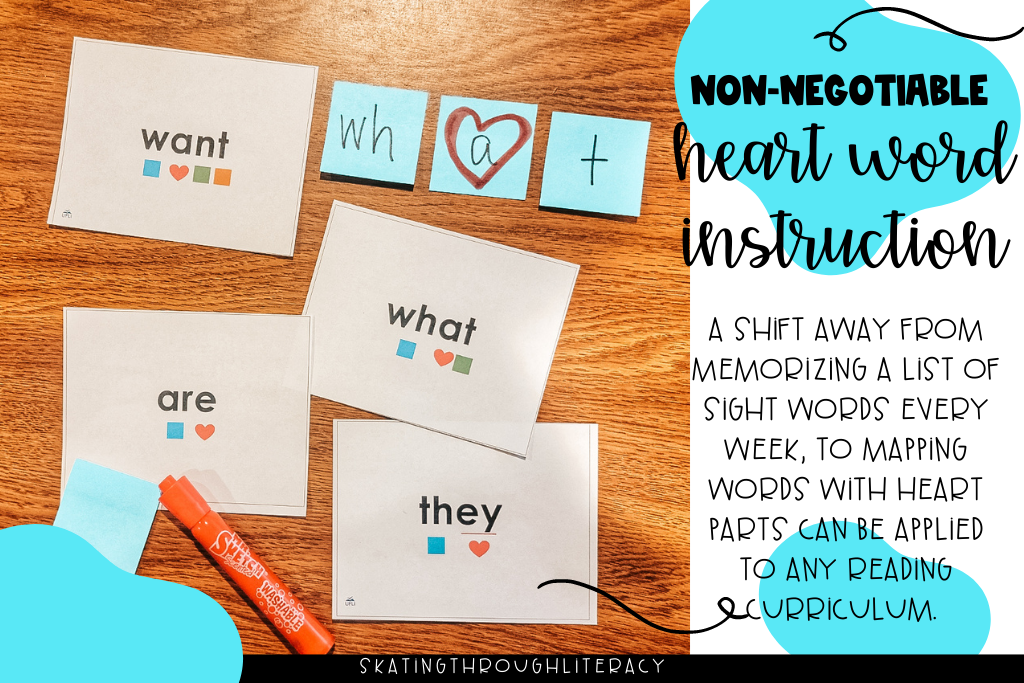

Non-negotiable #2: Heart words replace sight words

I’ve always taught in a district that was curriculum heavy. Every week there would be a list of “sight words” or “high frequency words” or something in which I was suppose to help the students memorize. I use to hold up flash cards and have students read them as fast as they could. Or go around the table and let each kid one at a time read a few. But this skill and drill of different words every week wasn’t making a difference. When I replaced this memorization of sight words with the instruction of heart words, I began seeing light bulbs go off.

As it turns out, most parts of a sight word are actually completely decodable. Often there will be just a letter or two letters making a sound you would not expect. By graphing the regular parts of the word, then drawing special attention to the irregular part, students commit to memory which letter represents the unexpected sound. Mapping words just a hand full of times was twice as effective as holding up the same flash card every day. If you want to know more about mapping heart words, be sure to check out this blog post where I go in depth with the how and the why!

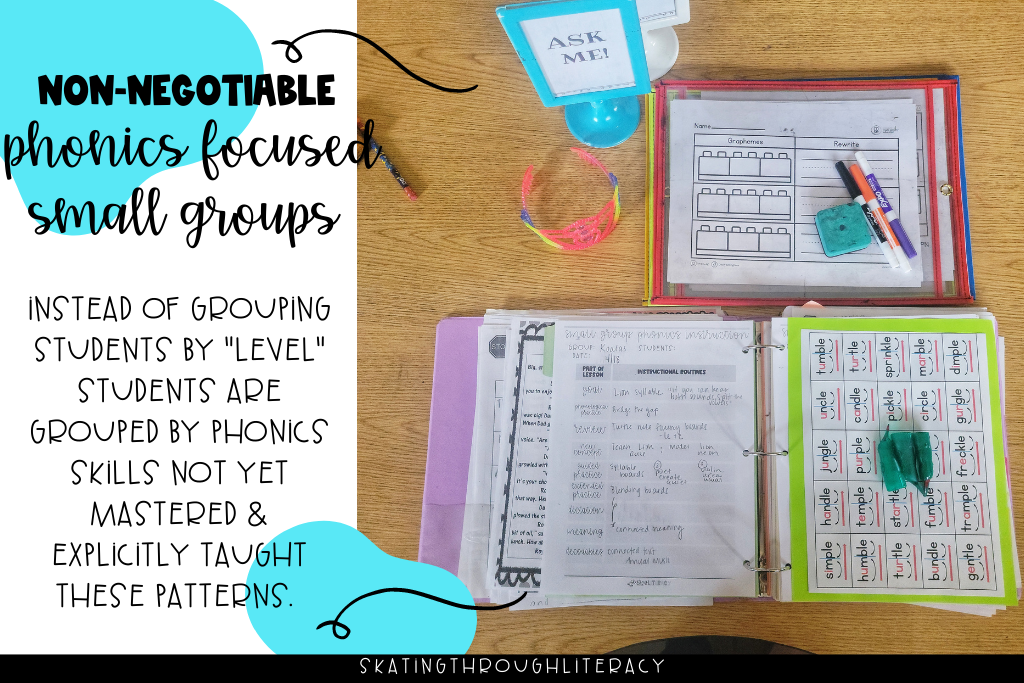

Non-negotiable #3: Small group instruction focused around phonics skills

For years, I taught guided reading groups based on the students reading level. I would give them all books at the H level. Teach them some strategy that wouldn’t actually help decode the words like “let’s visualize about this book.” Then hopelessly listen to them read as they missed words and I pointed to the picture hoping the prompt would help them guess it right. A huge shift in moving from balanced literacy to a reading block with the science of of reading in mind is this move towards explicit phonics small groups.

Now, any student reading below grade level, is assessed to find the skills they are still lacking to be a fluent successful reader. Then students are placed into groups to specifically target that skill they are missing. The skill is then explicitly taught, modeled, practiced, read, and applied in a variety of ways until mastery. This shift in small group instruction allows students progress through the skills. If you’re looking for the lesson plan I use, or how I plan this instruction, be sure to check out this post where I share the ins and outs. This ultimately supports their journey to be successful readers by providing explicit instruction in how to decode the words.

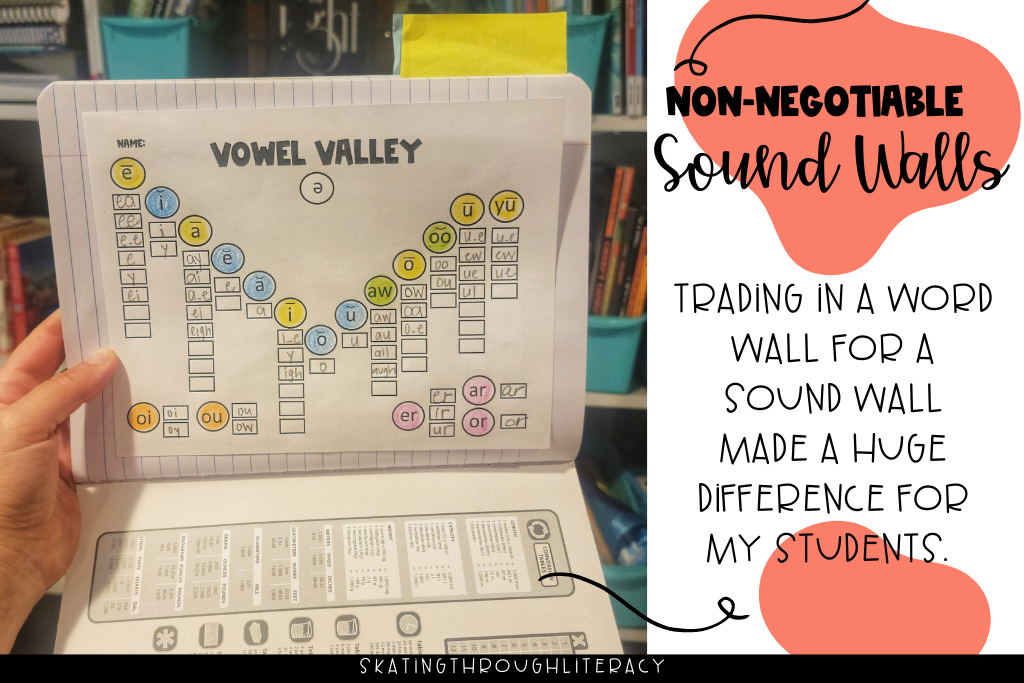

Non-negotiable #4: Sound Walls

Really, this non-negotiable goes hand in hand with heart words. Much like memorizing high frequency words, a word wall is filled with words once memorized slapped up in abc order. Doesn’t matter that goat and giraffe both start with g and make completely different sounds. They start with g, so that’s where they went. This can be so confusing for a student who is struggling to figure out what sounds in words are and what letters to use to represent those sounds.

Now, when introducing our phonics pattern for the week, we start with the sound. We talk about how to articulate the sound and make it with our mouths. Then, we discuss what letters we know in English that could represent these sounds. Next, we’ll learn any rules we know about when to use different letters that represent the sounds we’re studying. Finally, we’ll keep track of all the ways we know to make different sounds. This instruction provides meaning behind why words work the way they do. Which is invaluable instruction to early readers, writers, and spellers.

If interested in adding a vowel valley or a consonant sound wall, you can check out the two I use in my own classroom on TpT!

Non-negotiable #5: Hands on opportunities everyday

By far my favorite part of incorporating the science of reading is all the hands on opportunities to build and work with words. We as teachers understand the value of hands on opportunities for our students. By using what we know about students and the value of tactile learning, we can incorporate important science of reading principles to our instruction.

The possibilities of hands on tools are limitless. I often would use materials I had around my classroom even for other subject areas, like these cubes for math. Adding in the tactile learning is another way to help students put concrete representation to their learning.

So now what?

Now that you’ve considered all these questions, and considered some of my non-negotiables, it’s time for me to remind you of the most important part of rethinking your reading block: and that’s to remind you that you are a fabulous teacher. If you’re here even reading this blog post, considering how you teach reading and what you could do more effectively; than you are a fabulous teacher that wants what’s best for their students. One of my favorite quotes when I began to dig deep into this work is “teaching reading is rocket science.” Good, high quality literacy instruction can’t be just looked up in a book or on a blog post. It takes continuous learning around science and brain development, reflection on the students sitting in front of you, a wide variety of classroom management skills, a well managed classroom environment, high quality texts and materials that support your teaching, the list goes on and on.

By reflecting on your current practice then identifying just a few small changes that could enhance what you’re already doing is a great first step. Thinking about your reading block with the science of reading in mind is a journey, not a destination. Remember we as teachers are also lifelong learners, just like our students.